LFF 2015: Trumbo ****

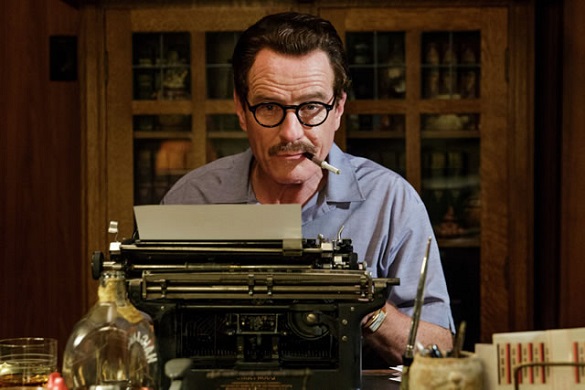

If there was any doubt left as to Bryan Cranston’s acting prowess after Walter White in Breaking Bad, his latest incarnation as blacklisted Hollywood screenwriter Dalton Trumbo will silenced that. Entitled Trumbo, director Jay Roach and writer John McNamara’s cinematic take on Bruce Cook’s book is another Cranston career highlight to date that has put him in the running for Best Actor gong at this year’s Oscars.

Tales of America’s deep-rooted fear of Communism always make for intriguing viewing, but this niche subject matter set in the Hollywood heartland might seem a touch self-indulgent and could take more of a sell at the box office for a non-American audience. Thanks to Breaking Bad, though, some might be persuaded to dabble.

However, Trumbo ought to be seen first and foremost as a story about freedom of expression, something that should never be taken for granted. It follows just that, the story of the hugely successfully screenwriter in the 1940s/50s who was blacklisted by the film industry for his alleged far-left views and jailed along with fellow colleagues.

In order to start working again on release, Trumbo re-penned new scripts for low-budget flicks under a pseudonym. Naturally, all became highly profitable at the box office in their own right – one even won an Oscar. This source of income allowed Trumbo to employ his down-on-their-luck writer friends. It was only after some big industry names took a chance on him in the 1960s that he was able to come back into the limelight, much to the disgust of snide gossip columnist – and ‘Commie outer’ – Hedda Hopper (Helen Mirren) who wielded a lot of power with studio bosses and fed the Red fear.

Cranston is consistently absorbing as Trumbo throughout, a complex mixture of self-assured warmth, brilliant wit and liberal-thinking, but also narcissistic and pig-headed, virtually driving his wife Cleo (brilliantly underplayed by Diane Lane) and young family away, as he imposed his crushing lifestyle on them – even ‘employing’ them in his new clandestine venture. Cranston’s charm radiates from the screen in Trumbo’s enlightening moments, causing you to fully realise the charisma of the man. Equally shocking are Trumbo’s moments of grandeur, though you admire his dedication to the written word.

Mirren as Hopper is delightfully conniving and despicably scheming, having blackmail down to a fine art while being the perfect opponent for Trumbo to clash with. There are many choice words exchanged between the two that keep the script bouncing along and highly entertaining, making Trumbo’s end triumph much sweeter.

The film suffers the same folly as any other that tries to get actors to portray big-screen icons. David James Elliott only just captures a youthful John Wayne’s essence but seems pitifully inadequate when up against Cranston’s Trumbo. Only Dean O’Gorman’s Kirk Douglas cuts the mustard in his Spartacus (1960) heyday, and that of Christian Berkel’s Otto Preminger – the director who took a chance on Trumbo with Exodus (1960).

Credit too, to Louis C.K. who sweats and frets it out as fictional screenwriter friend Arlen Hird, Trumbo’s greatest critic and voice of reason. Hird feels like a real-life character because he is based on real-life communist screenwriters Samuel Ornitz, Alvah Bessie, Albert Maltz, Lester Cole and John Howard Lawson.

John Goodman is a fizzy tonic as the blunt, headstrong small studio boss Frank King too, providing some of the lighter, funnier Trumbo altercations – and sticking it to the ‘big boys’.

Trumbo is highly stylised to match the era, even glossy in cinematography, fully immersing you in that environment, while striking a chord with Film Noir fans in Trumbo’s darker moments. It’s a piece of cinematic competency, in acting and production – definitely one for Cranston fans not to miss.

4/5 stars

By @FilmGazer