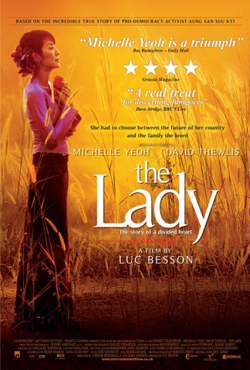

The Lady **

Visionary French director Luc Besson is no stranger to developing utterly compelling stories centring on intriguing female protagonists, and delving into the make-up of their psyche during their individual struggle, from adults (Nikita) to children (Leon). Therefore, with the story of what made one of history’s most iconic female figures, Burmese pro-democracy fighter Aung San Suu Kyi tick at his fingertips, Besson has surely struck cinematic gold? Disappointingly not, even if charismatic actress Michelle Yeoh is present to help translate Daw Suu’s remarkable political and personal journey.

Visionary French director Luc Besson is no stranger to developing utterly compelling stories centring on intriguing female protagonists, and delving into the make-up of their psyche during their individual struggle, from adults (Nikita) to children (Leon). Therefore, with the story of what made one of history’s most iconic female figures, Burmese pro-democracy fighter Aung San Suu Kyi tick at his fingertips, Besson has surely struck cinematic gold? Disappointingly not, even if charismatic actress Michelle Yeoh is present to help translate Daw Suu’s remarkable political and personal journey.

The story is one of a ‘fairy-tale’ love story staged across faraway lands between Daw Suu (Yeoh), the daughter of Aung San, the alleged ‘father of modern-day Burma’, and English Oxford University professor Dr. Michael Aris (serviceably played by David Thewlis). After returning to her homeland, military-junta-controlled Burma to tend to her sick mother, Daw Suu is appalled by the murderous atrocities she witnesses and decides to stay and lead the democratic movement, leaving her family life back in Britain. As her following grows, Daw Suu is deemed a significant threat to the establishment, and placed under house arrest, restricting access to the outside world – and her cancer-stricken husband.

Curiously, Besson sets the story from the point of view of a dying man, already targeting the heartstrings of a ‘love that cannot be’. This is further emphasised by the little Suu Kyi being told a fairy-tale by her father at the start, that his little princess will one day find harmony in a peaceful, idyllic land with a prince of her own. There is nothing wrong with the love-story angle whatsoever – sweeping us up in the process, and this was never going to be a dense biopic about the political oppression Daw Suu actually suffered. However, in keeping things ‘romantic’ rather than more raw when necessary, Besson dilutes the harrowing and far intriguing side of why such a woman chose her country over her young family? This is never fully explored to highlight the full sacrifices both parties made, merely depicted with scenes showing Aris’s grumbles over his visa refusals and a couple of hugs in the Burmese evening air for the pair. The result is the opposite effect to what Besson is angling for: a near passionless affair.

It’s only the performance from the enigmatic Yeoh that gives any of the status quo any viewing power. The Kong Kong actress and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon star brings that respectful composure and soothing karma to the role of Daw Suu that both her and her heroine exude. Frustrating as it is to not find out more about her character’s personal drive from Besson’s film, Yeoh is still very much Daw Suu in the flesh, both physically and in temperament. Besson does suggest Daw Suu’s rise was all too easy here, in that merely making a peaceful appearance and taking a defiant stance facing the barrel of a gun was enough. It demonstrates a reluctance to show the ugly side of politics and possibly sully any of Daw Suu’s deity-like standing, reemphasised in the film’s simplistic fairy-tale stance. There are never any realistic initial confrontations between man and wife, considering Daw Suu is choosing her countrymen over her husband and sons. In Besson’s defence, he does show how the situation and her rise to notoriety crept up on the Arises, before the point of no return. It just seems a trifle unbelievable that there would not be more family fallout, however courageous and inspiring the mother is.

The only real drama, amidst the cartoonish and superstitious capers of the deranged Burmese leader, General Than Shwe (Agga Poechit), is the moment captive Daw Suu tries to hear her family receiving the Nobel Peace Prize on her behalf in 1991 over the radio, and after the mains are switched off deliberately by the military, she and her housemaid use some batteries from their torch to power the device – all reminiscent of the British bulldog spirit in the war years. In hindsight, the lump-in-the-throat at this moment is more due to the real-life worthy recipient, rather than the film’s actual portrayal, although Besson builds this momentous and joyous/sad event nicely, in his ardent respect for his leading lady.

The Lady is Besson’s own love story, in fact, to his political heroine and more than well intentioned. It is virtually impossible not to rally behind Daw Suu and want retribution for the injustices that the film touches on, especially with such a solid performance from Yeoh, who ought to get her own awards recognition for her detailed and convincing portrayal of Nobel winner Daw Suu. Although hardly surprising on political persuasion, the film is never dogged and forthright in showing some of the true horrors to further condemn the country’s stagnant political situation – even though no one is expecting a recreation of the haunting real-life scenes captured in Anders Østergaard’s Burma VJ either. It’s just the lack of any real sense of danger lessens what could have been a far more impacting film by a filmmaker who is usually an expert at such.

2/5 stars

By @FilmGazer