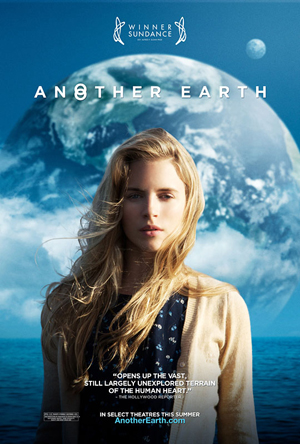

Another Earth ****

Sundance winner Another Earth is as ambiguous as its trailer, but at its indie heart is a tale of tragic redemption, rather than apocalyptic sci-fi curiosity. Listen carefully to the trailer voiceover, as this is one girl’s journey laced with an otherworldly presence.

Sundance winner Another Earth is as ambiguous as its trailer, but at its indie heart is a tale of tragic redemption, rather than apocalyptic sci-fi curiosity. Listen carefully to the trailer voiceover, as this is one girl’s journey laced with an otherworldly presence.

On the night of the discovery of a duplicate planet to Earth in the solar system, an ambitious young student called Rhoda (Brit Marling) and an accomplished composer and university professor John Burroughs (William Mapother) cross paths in a tragic accident. What happens next is down to Rhoda’s actions and Burroughs’s reactions.

Documentary filmmaker and writer-director of this tale Mike Cahill presents an alluring sci-fi moral full of humane fragility that draws a touchingly mesmerizing and soulful performance from its lead, Marling. In its pseudo-documentary style, it seeks a grounded realism, considering its parallel sci-fi furore and ethereal quality, which can only be as a result of Cahill’s filmmaking background.

Indeed, Another Earth could be described as ‘another Melancholia’ in concept, where Rhoda, a young girl in a depressed trance seeks solitude from society’s harsh judgement of her by tackling her grave human error by embarking on a kind of ‘restorative justice’. The Earth 2 is both her reality and her metaphor for the second chance that she realises she craves. It’s also the cause and the cure of her situation, resulting in an open-ended finale that’s up for intelligent debate.

Cahill’s casting of Marling opposite Mapother (of Lost fame) is utterly magnetic and the sole power behind the tale. These two distressed characters’ immediate worlds collide and provide a temporary lifeline for each other, away from the obsessions of the rest of civilisation. It’s here that Cahill allows the tentative steps towards their union to develop, creating an almost inert atmosphere to do so, resulting in both coming alive in this artificial environment then shutting down outside of it. It’s a fascinating transformation.

The inevitable truth cannot be kept at bay, which acts as a catalyst on the road to healing for both characters, to assimilate them back into society. The start of their journey may well be seen in the trailer, but it provides an incredibly blunt and dramatic shock tactic very early on in a film of two worlds colliding, both physically and metaphorically. It’s also refreshing to have a seemingly well-adjusted and fortunate youngster and a female as the delinquent for a change, which may be why Cahill’s film could feel unique – like a tabloid reporting on the more ‘attractive victim/culprit’ to grab and sustain attention.

Nevertheless, the power of the human mind to overcome adversity in its own way, whether that’s away from society rule is what gives Cahill’s film such inquisitive appeal. The sci-fi is merely a contributing factor to what is in effect a robust character study of salvation.

4/5 stars

By @FilmGazer