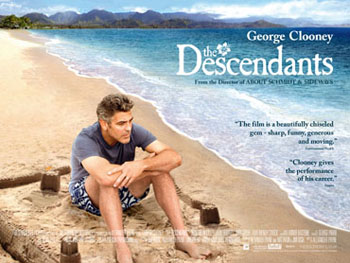

LFF 2011: The Descendants *****

It’s Hawaii – but not as we know it. Writer-director Alexander Payne has set one of star George Clooney’s most anticipated releases, The Descendants – since its unveiling at the BFI LFF 2011 – in paradise. But it’s a paradise of a viewing kind that is the perfect combination of dramedy, tragedy and familiar fallouts that simultaneously brings tears of joy and sorrow, with seemingly effortless effect. And with a sprinkle of the Clooney magic in this, its possibilities are endless for the route the story will take.

It’s Hawaii – but not as we know it. Writer-director Alexander Payne has set one of star George Clooney’s most anticipated releases, The Descendants – since its unveiling at the BFI LFF 2011 – in paradise. But it’s a paradise of a viewing kind that is the perfect combination of dramedy, tragedy and familiar fallouts that simultaneously brings tears of joy and sorrow, with seemingly effortless effect. And with a sprinkle of the Clooney magic in this, its possibilities are endless for the route the story will take.

Matt King (Clooney) is a workaholic lawyer who has lost touch with his wife, Elizabeth (Patricia Hastie), and his two teenage daughters, Alexandra (Shailene Woodley) and Scottie (Amara Miller). After a freak boating accident that hospitalises his spouse, King must reconnect on his less-than-idyllic home life. But in doing so, dark secrets bubble to the surface, while King must decide on whether to sell his family’s prized strip of sun-kissed Hawaiian land to property developers.

Admittedly, in one of Clooney’s most perfect castings to date that has seen the actor get nominated for Best Actor at the Oscars this year, as well as take the Golden Globe for Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama, Clooney is given the opportunity to focus on all the screen characteristics that make him so appealing, all within an anti-charm offensive. King is by no means an instantly ‘likable’ character – overcoming the envy at his surroundings, his flaws are more apparent than his positives. However, the lure of the scenery plays wonderfully in contradiction with the daily troubles of a man who pretty much ‘comes of age’ in this story, re-learning some long-forgotten life lessons and priorities. As we go along on King’s journey, we grow very fond of him and all he has accomplished, and his ‘rebirth’ leaves you with a huge sense of fulfilment and ultimate joy – plus there is a lot of laughter along the way.

Payne’s film has an almost naturalistic flow to it – like tuning into a reality TV show about the goings-on in the Hawaiian ‘burbs. Again, Clooney’s easy manner works a treat in this setting, but not without the story’s little antagonists to break the lush daydream. US TV actress Woodley has made a big impression after this – including being nominated at the Golden Globes. She expertly hones her sharp and dry comic retorts with that of Clooney’s, especially in one of the funniest, quirkiest comedy duo scenes in a long time, when father and eldest daughter confront sleazy property developer Brian Speer (Matthew Lillard) on the porch of his holiday condo. Nick Krause is your typical, irresponsible teen as dopehead Sid, who ironically starts to make more sense in King’s topsy-turvy world than the things he used to hold dear.

Judy Greer as Speer’s cheated wife comes into her own – with a subtle supporting effort from Clooney – in Elizabeth’s hospital room, in a heart-wrenching confessional that is laced with black humour. In fact, Payne and co-writers Nat Faxon and Jim Rash have stayed fairly true to Kaui Hart Hemmings’ touching novel, really getting the essence of what makes these characters work, and picking up on some highly astute observations that anyone in their situation would want answers to and react as such.

Payne’s The Descendants is intelligent comedy, never trying to coerce the situation into gaining some false laughs where they are unjustified, or gratuitous within the seriousness of the moment. Its relaxed tone – a delightful far cry from the situations you and the characters are faced with – is replicated throughout right to the very end that is a curious scene, but one that succinctly concludes the family’s next chapter. This is a Clooney triumph not to be missed.

5/5 stars

By @FilmGazer